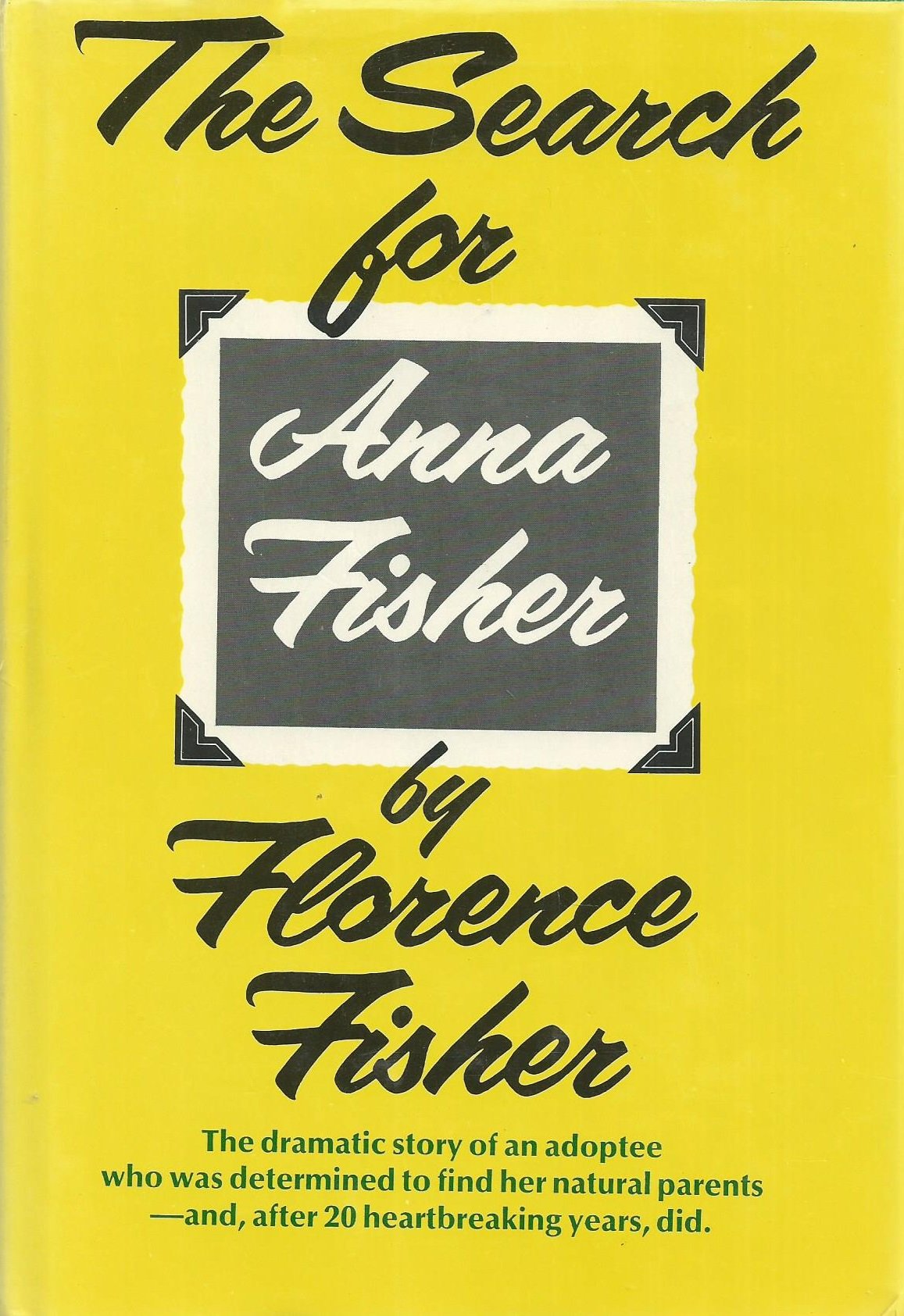

The Search for Anna Fisher

by Florence Fisher

Arthur Fields Books, 1973

Reviewed by Barbara Free, M.A.

In 1976, my mother gave me this book, which she had just read. I had relinquished my first son in 1966 and subsequently married and had three children. She was terrified that I might someday try to find my first son, so it is surprising she gave me the book. I read it immediately. I had always known I would search and find him, but I never mentioned it to her. The idea of legally searching, or having search or support groups, was pretty much unknown.

Florence Fisher was the founder of the Adoptees Liberty Movement Association, so named so that the acronym would be ALMA, which means “soul” in Spanish.

She had been adopted as an infant by an ultra-orthodox Jewish family, who never told her she was adopted. Her adoptive mother would even describe her “horrible labor and delivery.” When Florence was seven, she found the adoption paper and asked about it, only to be verbally and physically abused by both adoptive parents. Her mother told her that was just a paper they were keeping for another relative.

She never forgot this, and had been quite puzzled since starting kindergarten, when her mother refused to let her see her birth certificate. She had no one to turn to who might tell her the truth. Her grandmother always pushed her away, calling her “momser,” which is Yiddish for “bastard.” They had been living in New York City until she was ten, when they moved to Philadelphia, which her mother did not want, and the father did not move there for another year. She had no idea what that was all about until years later, when she found, in her searching, that she was born in Philadelphia.

As Florence grew up, she was increasingly unhappy and kept wondering about her parents, and if she, in fact, was adopted, and why. Not knowing what else to do, she got married just out of high school her parents had told her they would not paying for her to go to college. She had been kept in a baby crib in her parents’ bedroom until she was ten years old, when her mother got her a “junior bed,” with rails on the side, “so you won’t fall out.” What few friends she was allowed to have were amazed that she was still expected to sleep in this little bed until she was 17 years old.

Her parents kept moving, back to New York and to different apartments. When she got married and had a son, she worried if he would be normal. She realized her marriage was a mistake, and wanted to get divorced, but her mother said, “You’ll disgrace us.” She had tried to forget the name “Anna Fisher,” which she had read on those adoption papers long before, because she was known as Florence Hadden. When her son was born, a nurse tried to cover her face during the birth and she yanked it off, saying, “I have to see my child born.” It was common in those days to give women general anesthesia, or if not, to try to keep them from seeing their child born. Many birth mothers still have a great fear of not seeing their children born, and of being unconscious and therefore out of control.

That same year, her mother began having all sorts of physical and emotional problems and was sent to a hospital for shock treatments, a very common remedy for women at the time. Her mother wanted to move in with her, which Florence did not allow. Soon, her mother began having difficulty moving, became more confused, and died. When her mother died, Florence told her she loved her. Her mother’s last words were “Now you’ll have no one.”

The relatives argued over who would get her mother’s jewelry and personal belongings, never considering that Florence, as her daughter, ought to have these things. Her father did not intervene on her behalf and yelled at her toddler son for crying. She called a friend to take her out of the house. Later, she called a cousin she trusted, who told that she was, indeed, adopted, but her parents had threatened to kill anyone who told her. After that, she began searching for her birth parents.

Most of the book is about her search, which was very difficult and took many years. She was refused information at almost every turn. During those years, she got a divorce, went to school, remarried, had a career, and continued to search, with her husband’s steadfast support. The book reads like a mystery novel, but it is, of course, not a book of fiction at all. Reading it again, more than forty years later, was just as compelling as the first time. She did, after many years of being threatened, lied to, and still persevering, find her records, her original name, and both of her birth parents. All was not rosy, as her mother was very fearful of anyone finding out she’d had this first child. She had been told her baby died at birth. She had remarried (she was married, briefly, when Florence was born), had two more children, and was afraid of their disapproval. When Florence placed an ad in a newspaper, which was the start of ALMA, her mother told her she could not see her again nor have further contact. She later found her birth father living in California, who was very excited and welcomed her with open arms. She also found out her birth mother had not named her Anna, but Florence, so she legally changed her name to Florence Fisher.

Her favorite adoptive uncle said he would have helped her in any way he could, had he known she was searching. She began having support and search meetings, speaking to adoptive parents groups as well as individual adult adoptees and birth parents. At the end of the book, she says “Everyone is somebody’s child. Everyone has a history—and that history can neither be denied nor ignored.” She went on to live to age 95, and died just a year ago, in October 2023. Elsewhere in this issue is a remembrance of Florence Fisher by Lorraine Dusky, a birth mother who became a close friend and fellow searcher and activist, working closely with Florence Fisher. The entire article is available on the Internet, where we found it.

Although this is not a new book, it is important historically and still relevant to all those who have searched, or been found, or have adoption connections. It is still available in the Operation Identity Lending Library, as is Lorraine Dusky’s own book, Birthmark.

Excerpted from the November 2024 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2024 Operation Identity