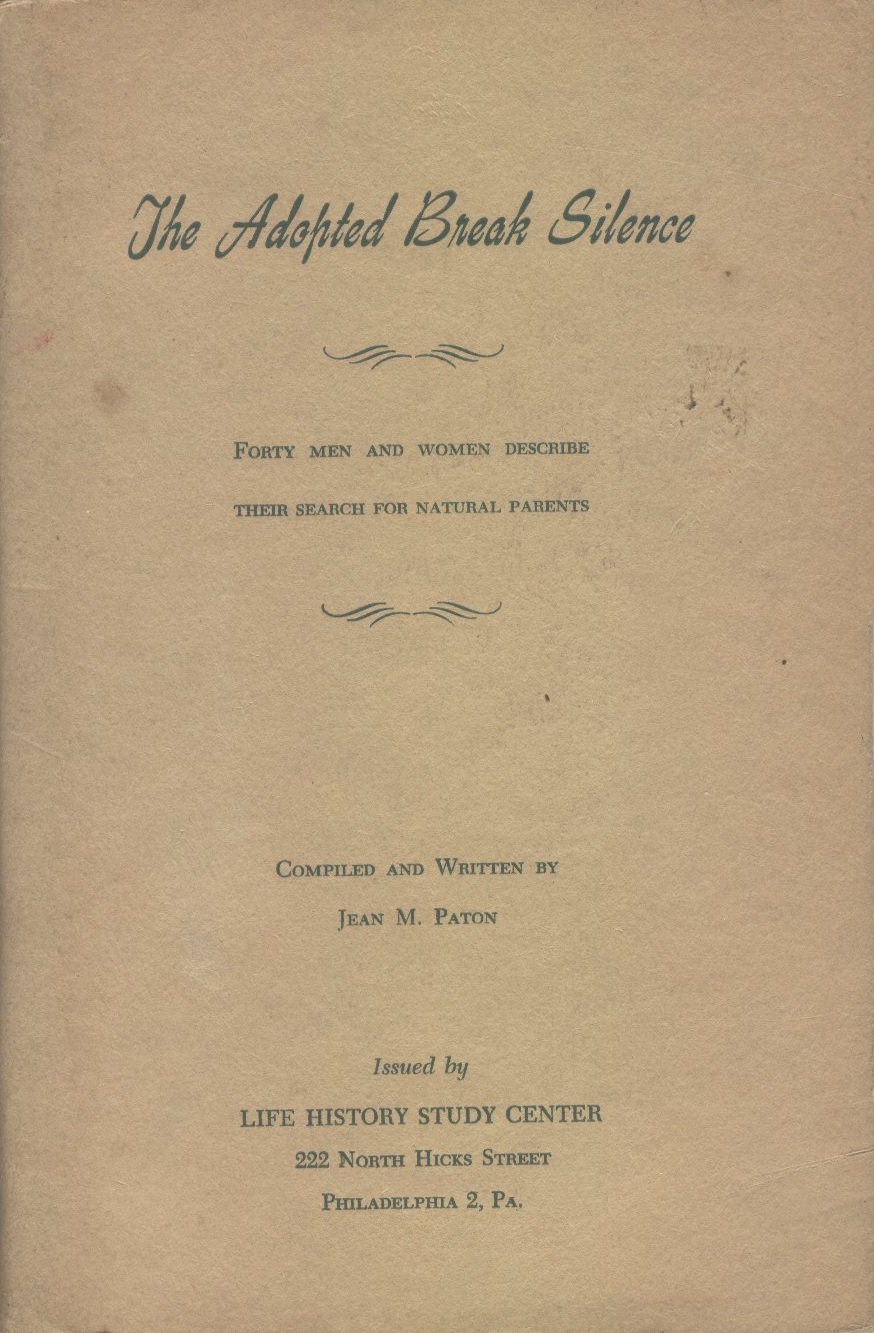

The Adopted

Break Silence

by Jean Paton

Life History Study Center, 1954

Reviewed by Barbara Free, M.A.

When she began to realize how traumatic adoption might be for some, and as she sought to find her own information, Paton decided to do research on persons who had been adopted. She went to Michigan, where she had been adopted, as well as Philadelphia, where she was living as an adult, to interview adult adoptees about their experiences. Excerpts from some of the interviews are in the book.

Paton also relates her own experience of being adopted, not once but twice, at five months old and again at 2½ years. The second set of adoptive parents tried to keep her from knowing she was adopted, and when she found the papers one day, they still denied it and were physically as well as verbally and emotionally abusive. She had one uncle who really cared for her.

In her interviews, she encountered some who had happy adoptive childhoods, some who did not, especially some who were on the “orphan trains,” largely picked by families who wanted them as free labor. Some of these adoptions turned out to be happy for the adopted person, but many did not. Other books in the O.I. library concern some of these cases.

Some of her interviewees expressed a desire to find birth family, or to learn about their own “nationality,” what we would now call ethnic background or genetic information. Some stated that they believed any mother who would give up a child, no matter the circumstances, was not worthy of consideration and not fit to raise a child.

The terms “abandoned” and “abandonment” were frequently used by those who held these views. The use of the term “illegitimate” is used a lot, including by the author, a term the adoption world, and much of society, no longer uses, as it is so negative and judgmental, implying the person has no right to exist. In reading this book, one must take into account that it was written in the early 1950s.

The information and the author’s serious consideration of various situations, including death of original parents or their inability to provide for too many children, is handled in ways that show her respect for those she interviewed. Paton strongly advises that adopted children should be told of their adoption very early on.

This book is a valuable record of her early research, and is best read in conjunction with her later book, Orphan Voyage, a review of which follows.

Excerpted from the February 2025 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2025 Operation Identity