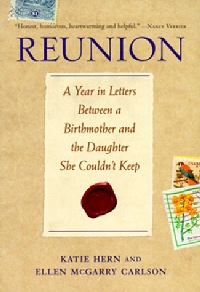

Reunion:

A Year in Letters Between a Birthmother

and the Daughter She Couldn’t Keep

by Katie Hern and Ellen McGarry Carlson

Seal Press, 1999

Reviewed by Barbara Free, M.A.

Both Katie Hern (the daughter) and Ellen McGarry Carlson are writers, which makes the letters quite articulate. Katie found Ellen, although Ellen had previously made an attempt at search. Massachusetts, where Katie was born and where Ellen still lives, was not an open-records state then, although it is now. However, Catholic Charities, the agency through which Katie’s adoption was processed, did have a policy whereby a birth mother could “open the file” to the relinquished son or daughter, and Ellen had done so. Therefore, Katie was able to obtain Ellen’s name and address, so no exhaustive search was needed.

Ellen had previously asked for information, but was just assured that her daughter was in a fine family and doing well, and should not be “interrupted.” There seems to be a universal fear of “interrupting” the adoptive family, the son or daughter, or, not as often, the birth mother, who is portrayed as hiding in shame forever, having never told anyone, not even a spouse, of her terrible transgression. In spite of open records, and even semi-open adoption, this attitude persists in society.

Katie starts the reunion process by writing to Ellen, who has been notified by Catholic Charities that her daughter has received her name and address. She begins by telling of a happy childhood and supportive parents, who do not know of her desire to find her birth mother. She also reveals that she is gay, in a committed relationship, and living in San Francisco. This was in 1996, prior to same-sex marriage laws. Ellen replies immediately to the letter, very excited about being reunited, and reveals that she is married with two young sons, a college student and writing tutor.

The letter exchange begins in early 1996, when Katie initiates contact, and documents the process as they get to know each other and explore their own and the other’s feelings, as each reveals more about herself, and they share their respective experiences and feelings, fears and hopes. Katie and Ellen work through their feelings and misgivings through letters and e-mails, and some telephone calls, although they both prefer writing. After some months, they meet in person, in Massachusetts, where Katie’s adoptive parents still live.

The reunion appears to go well, but Katie is upset and withdrawn afterward, only gradually realizing that it stirred up more feelings than she could handle, and led to a strain between her and her adoptive parents, especially her mother, who, it turns out, was not at all supportive of the reunion; she was quite jealous and actually hostile toward the very idea of ever meeting Ellen in person, which eventually she did. Over the course of the first year, they visit again, more than once, in person. Ellen’s husband and sons are quite taken by Katie, and Ellen really likes Katie’s partner, Cara. Katie begins to reveal more about her childhood, which was not as rosy as she portrayed at first, and Ellen begins to discuss her own childhood with an alcoholic father.

Several things stood out to this writer. The first is that Katie, the daughter, is at all times, in charge of the progression of the relationship, how close, when to meet, what feelings or expression of them, is allowed. This is subtle, but definite. Ellen is adaptable, more often cautious, although not always. Even at the end of the book, and even in the Afterword written two years later, Katie is angry and says Ellen could have “made another choice” to keep her, not acknowledging the impossibility of that for a twenty-year-old Catholic girl in 1969. Ellen remains happy and “grateful” at having Katie back in her life, and appears never to defend herself against others’ resentments, including the adoptive parents’ refusal to get to know her. These dynamics are consistent with many other reunion relationships, especially the fact of the son or daughter’s being in charge of the relationship, consciously or not.

The other significant dynamic is that both are female, so they may be more in tune with each other’s feelings and freer to express them than if Ellen had relinquished a son, or if Katie had found her birth father. Because both are writers, which enabled them to express themselves in letters, which, they both acknowledge, led to a deeper exchange early on. Both had left their extremely restrictive Catholic upbringing behind, in different ways. In the course of that first year, Katie was able to quit being, in her words, “the Adopted Child Poster Child,” and Ellen was able let go of her grief, which she had seen as shame, and reveal to family, friends, anyone interested, that she was a birth mother. The exchange of letters seems to have been very important in helping both of them come to terms with themselves.

This book would be helpful to other birth parents and adoptees, and adoptive parents, as they contemplate reunion, or as they experience reunion, even many years down the road, because of the thoughts and feelings expressed, as well as the events that take place. One wishes for a sequel, to find out how things are going now, nearly twenty years after the initial reunion. It would also be a good book for therapists to read, to know better how to help persons with adoption connections.

Excerpted from the July 2015 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2015 Operation Identity